Post 19: Remembering the past and re-imagining the future of food studies

The Canadian Association for Food Studies (CAFS) held its 2025 Congress at George Brown College (this deserves to be a topic of another entry) as part of the Congress of the Federation Humanities and Social Sciences (FHSS). The Congress is the largest academic gathering in Canada. FHSS was formed in 1996 through a merger of the Social Science Federation of Canada and the Canadian Federation for the Humanities. It represents over 85,000 researchers in 81 scholarly associations, 80 universities and colleges, and 6 affiliates across Canada.

Congress 2025 began on May 30 and will conclude on June 6. While they provide an opportunity for meeting colleagues and hearing presentations on diverse topics, Congresses have become too large; university funding has become more limited, and many societies have started to avoid Congresses as they have become too expensive. This could be the last face-to-face congress. Federation cancelled its 2020 Congress due to COVID and held the 2021 and 2022 Congresses virtually.

CAFS was founded in 2005. It participated in the Congress for the first time in 2006 at York University and became a member of the FHSS in 2008. I was the first President of CAFS, serving from 2005 to 2008. I rejoined the CAFS Board in 2024. The organization has undergone significant changes in its goals and management structure.

Along with two of my colleagues, I presented a paper at the CAFS conference discussing the history of the organization, reflecting on a study we conducted between 2008 and 2010. This entry benefits from our presentation (Mustafa Koc, Özlem Güçlü-Üstündağ and Atakan Büke). kgrounder. Of course, like most reminsences,

Since its inception, CAFS has sought to foster research that considers historical, political, ecological, economic, socio-cultural, and artistic concerns and sensitivities from a critical and systemic perspective. I have written in my past posts about my reminiscences of the early years of CAFS (20th Anniversary of the Canadian Association for Food Studies), and Chair of Food Secure Canada (On being a tree planter)

Organizational record-keeping is recognized as a key strength of bureaucratic organizations. With their focus on formal structures, rules, and standard operating procedures, bureaucratic organizations actively create and maintain records that serve as a repository of organizational memory. When I examine the CAFS website, I do not see any record of our past other than the programs of past conferences which, I am sure will be very valuable for future research to examine the intellectual transformation of CAFS. Very few organizations keep a record of their history. The Agriculture and Human Values Society is one exception I can think of.

Organizational memory refers to the accumulated body of data, information, and knowledge created during an organization's existence. Organizational memory is maintained through both its members and its records. Organizational memory is maintained through both its members and its records.

However, like many “ideal-typical” conceptualizations, good record keeping may not always be true. Unfortunately, particularly voluntary and civil society organizations (CSOs) have often suffered from organizational amnesia. One of the key reasons for this vulnerability is the rapid staff turnover rates in voluntary and civil society organizations. Another frequent problem is the failure to maintain accurate records and transmit them to new administrators. With new managers or a new board of directors, organizations revise their action plans, objectives, and management structure. Restructuring may improve things, but it can also be confusing, and new members may not know which changes were introduced, when, and for what reasons. Our over-reliance on IT, data management systems, and digital archiving creates new vulnerabilities due to the disappearance of records or experiential (tacit) knowledge that is hard to digitize. We also recognize that our best efforts to transmit experience to new members may often lead to information overload, which can hinder effective information processing. Finally, remote online participation can also create memory gaps and lead to ineffective communication.

This reminds us of the importance of archives, the supposed strength of bureaucratic organization. Still, many organizations do not maintain perfect records. Even when records were kept diligently, they remain in the archives as administrators do not want to overwhelm their websites with too much content and create confusion among readers.

Here is a comparison of the organizational goals of CAFS from 2005 and 2025. As you can notice, while some of these key principles remained the same, there have also been significant changes. Remembering these changes is crucial for maintaining a record of organizational transformation. It is also essential to understand the historical context that led to these changes.

In a survey of CAFS members during 2008-2010, we asked them to identify key aspects of food studies. The four key characteristics we heard were

Food studies focus on the entire food system,

It carries multilevel social science sensitivity with a focus on historical specificity, cultural diversity and geographical/spatial variations,

It has applied and/or transformative character,

It has an inter/transdisciplinary nature.

According to our 2009 survey, CAFS faculty/researchers were commonly housed in departments of nutrition (27%), geography (18%), environmental studies (14%), and sociology (14%). I wonder if this remains true today as well.

Canadian Food Studies:

CAFS has had its journal, Canadian Food Studies, since 2014. In a recent communication, Ellen Desjardin shared this note with me:

“In 2012, we announced at CAFS (WLU) that we had an editorial committee for CFS, and throughout 2013, we (David Szanto, Wes Tourangeau, Rod MacRae, Phil Mount and I) worked together to establish the framework, protocol, criteria, and active platform for the new online journal.

That year, we invited submissions for the debut issue and had them peer-reviewed and copyedited. Although the first published issue was in 2014, I began as editor in 2013. I continued until 2019, when we got funding from SSHRC. It was a huge learning journey for us all, and it continues!”

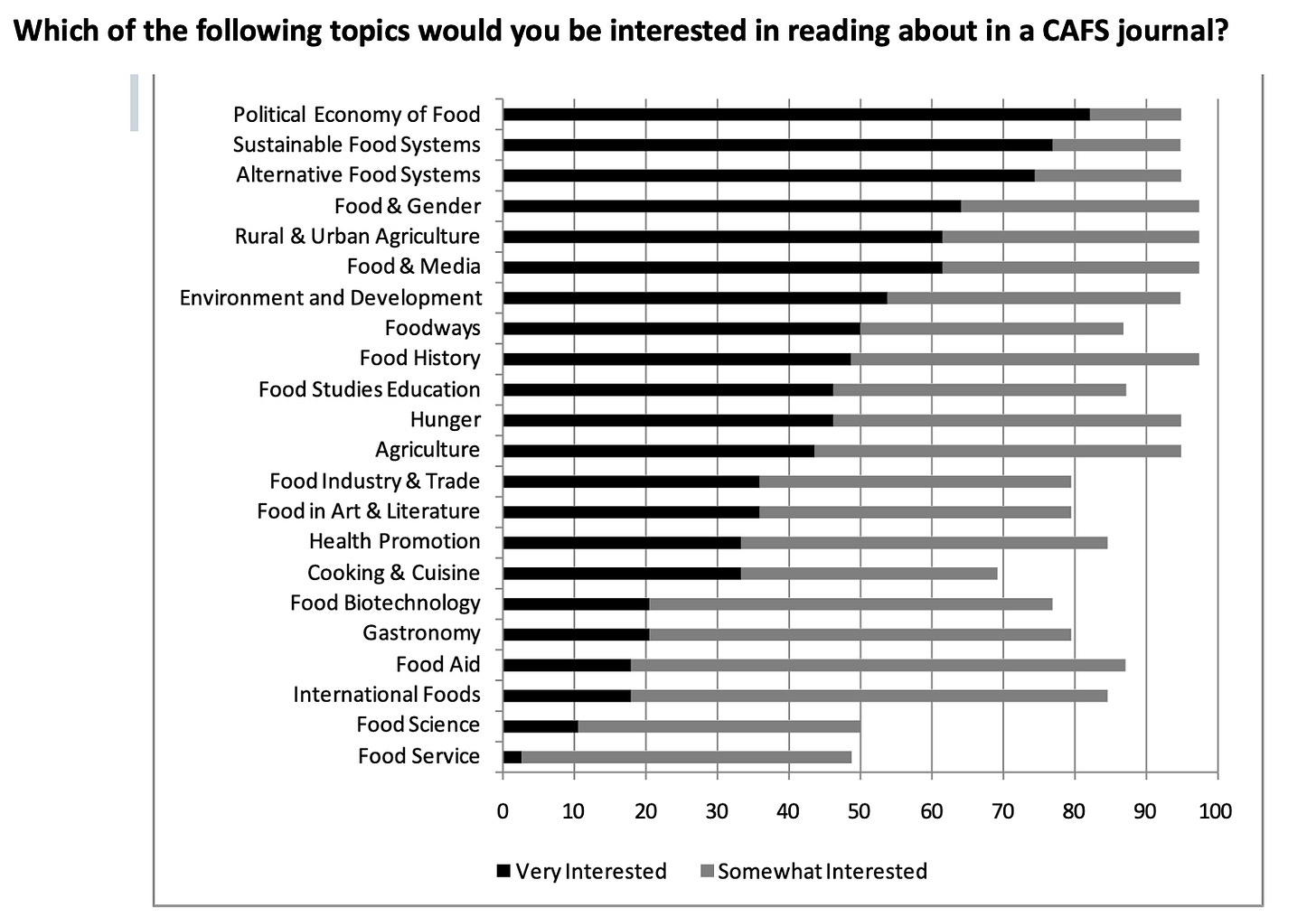

In 2009, the top five research priorities that CAFS members wanted to read in a CAFS journal were: political economy of the food, sustainable food systems, alternative food systems, food and gender and urban and rural agriculture. It is worth exploring how these priorities have changed over the years.

We cannot imagine a consensus among CAFS members or the editors of the CFS on what constitutes food studies or what kind of research should have priority for publication in the CFS. This tendency can be true for many scholarly organizations or journals. Indeed, it would not be an exaggeration to suggest that there are multiple food studies with varying intellectual orientations.

Organizations like CAFS must conduct periodic surveys among their members to identify emerging research and learning priorities and concerns, and to respond to the changes their members demand. It is also essential to recognize that there is a delicate balance between providing intellectual mentorship to new members and responding to the changes they require. A scholarly association like CAFS needs to operate like a school that is reflective of the demands of its members, while spending time in

The key concerns and research priorities of professional organizations continually evolve in response to historical developments, social, political, and economic challenges, as well as the prevailing intellectual debates of a specific historical period. Maintaining a record of these changes will aid in recalling the past and envisioning the future.