In January 1989, Canada and the US signed a Free Trade Agreement (FTA). Five years later, on January 1, 1994, it was replaced by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which eliminated most tariffs on trade among the US, Canada, and Mexico. Its supporters see it as a win-win-win situation, claiming all will benefit from it. Opponents of NAFTA in Canada and Mexico argued that NAFTA would punish small producers and workers and would result in an increase in reliance on imported foods, an overreliance on a single market, and the tailoring of domestic output to continental demands instead of local ones.

In the end, the free traders created a continental market. However, free trade only meant freedom to move goods, services, corporations, and corporate managers between borders. Farmers and workers were not free to move unless they were lucky enough to get visas as temporary migrant workers.

In the late 1980s, when the free trade negotiations were deliberated, food security or food sovereignty discourses had not yet been circulated. In the 1996 World Food Summit, the peasant organization La Via Campesina introduced the concept of food sovereignty as a counterargument to FAO’s food security policy. The Nyéléni Forum in Mali further refined what food sovereignty means. Declaration of Nyéléni, adopted on February 27, 2007, defined food sovereignty as “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.” I will get back to this debate in my later columns. However, I see these two concepts as complementary and food sovereignty as a requirement for food security.

The impacts of free trade on the agri-food system presented a similar pattern in all three countries: Mexico, the US and Canada. NAFTA’s effects in Mexico were quite dramatic in its first decade: around two million family farmers had to leave their farms, 20 million Mexicans were living in ‘food poverty,” twenty-five percent of the population did not have access to basic food, and one-fifth of Mexican children suffered from malnutrition. (Carlsen, 2013) Possibly the worst hit were the corn farmers, who could not compete with the highly subsidized US corn. “For those that did not lose their jobs, monthly income for self-employed farmers fell from 1959 pesos a month in 1991 to 228 pesos a month” (Women’s Edge Coalition, 2003). While subsidized US corn hurt corn producers, the price of tortillas, a staple of poor Mexicans, increased by 279 percent (Garcia-Galindo, 2023). Once fully self-sufficient in corn production, Mexico became a net importer of corn. Some former farmers found jobs in the new free trade zones called Maquilas, where unions and environmental regulations did not exist. Others moved up north to the US or Canada as seasonal farm workers. Migration Policy Centre (MPI) reported that Mexican immigrants increased from 2,199,00 in the 1980s to 4,298,000 by the 1990s and 9,177,000 by the 2000s. According to Statistics Canada, there were 278,377 seasonal farm workers in Canada in 2022; 44.3 percent were Mexican, and 25.2 percent were Guatemalan.

Immigrant Population from Mexico in the United States, 1980-2023

(Source: Migration Policy Center)

The impacts of NAFTA on Canadian farming were equally challenging for small and mid-size family farmers. According to the National Farmers Union (NFU, 2017), one in five farms has disappeared since 1988, despite the increase of 9.5 million in Canada’s population. In 2020, 51.5 percent of total farm operating revenues came from just 4.1 percent (7,746) of farms belonging to the $2,000,000 and over revenue class. Non-family corporations made up 2.4 percent (4,591) of all farms in Canada but reported generating nearly three-quarters (74.3 percent) of operating revenues (Statistics Canada, 2023).

Farmers were getting less for their produce while consumers were paying more for food. Between 1988 and 2016, farmers got 10 percent less for cows and 20 percent less for steers, while the price for ground beef nearly doubled. In 1988, wheat farmers received 20 cents for a $2 loaf of bread and 13 cents per $3 loaf in 2016. Farmer cooperatives that controlled 60 percent of Canada’s grain-handling capacity had disappeared by 2016, and 3 private multinationals own over half of the capacity. In 2012, the federal government terminated the single-desk authority of the Canadian Wheat Board (CWB), which had controlled wheat and barley marketing since 1935. CWB had been the target of global grain traders for a long time. In 2015, the federal government sold 50.1 percent of the CWB to Global Grain Group (G3), a joint venture between Bunge Canada and SALIC Canada—a Saudi Agricultural and Livestock Investment Company subsidiary. In 1988, there were 199 beef packing plants in Canada, and by 2013, 95 percent of the beef slaughter capacity was owned by Cargill and Brazil’s JBS (NFU, 2020).

The win-win-win rhetoric soon changed to “there are always winners and losers in globalization” in the biggest partner of the North American free trade pact. Angry “Rust Belt workers” who lost their jobs due to deindustrialization combined with free trade benefitted Trump, who promised to rip up NAFTA during his first Presidential campaign (NPR, 2017). "The net effect of trade agreements like NAFTA is to put more power, more authority with the large multinational companies and by extension, take that power away from family farmers," argued the National Farmers Union (US.) President Roger Johnson (NPR, 2017). The 2022 US Farm Census showed that the number of farms with sales greater than $5 million nearly doubled since 2017, and 78.3 percent of the total production value generated was from farms with at least $1 million in sales, even though those farms only represented 5.5 percent of operations. Farm Census results also showed that the total number of farms in the US decreased from 2.20 million in 2007 to 1.9 million in 2022. Many of those that ceased operations were mid or small-scale farms with sales between $100,000 and $500,000 or less than $10,000. The “get big or get out” policies of the governments and the political and economic power of the Big Agribusiness were blamed for these results (Center for Responsible Food Business).

The concentration ratio (CR) indicates competitiveness in an economic sector. When the big four companies control more than 40% of the market, we can no longer discuss a competitive market. Corporate concentration in the US agri-food system has worsened since the 1980s. The table below, by Mary Hendrickson and Phillip H. Howard, provides patterns of corporate concentration in the US agri-food system as of 2020. With mergers and inter-trading among these corporate players, following these data can be a never-ending detective game.

US Market Concentration

The US was the first country to introduce a food bank (St. Mary’s) in 1967. As in Mexico and Canada, food insecurity has remained a significant problem in the US. In 2023, the USDA announced that 13.5 percent (18.0 million) of US households were food insecure. Feeding America, a nationwide network of 200 food banks, announced that more than 47 million people, including 1 in 5 children, faced hunger.

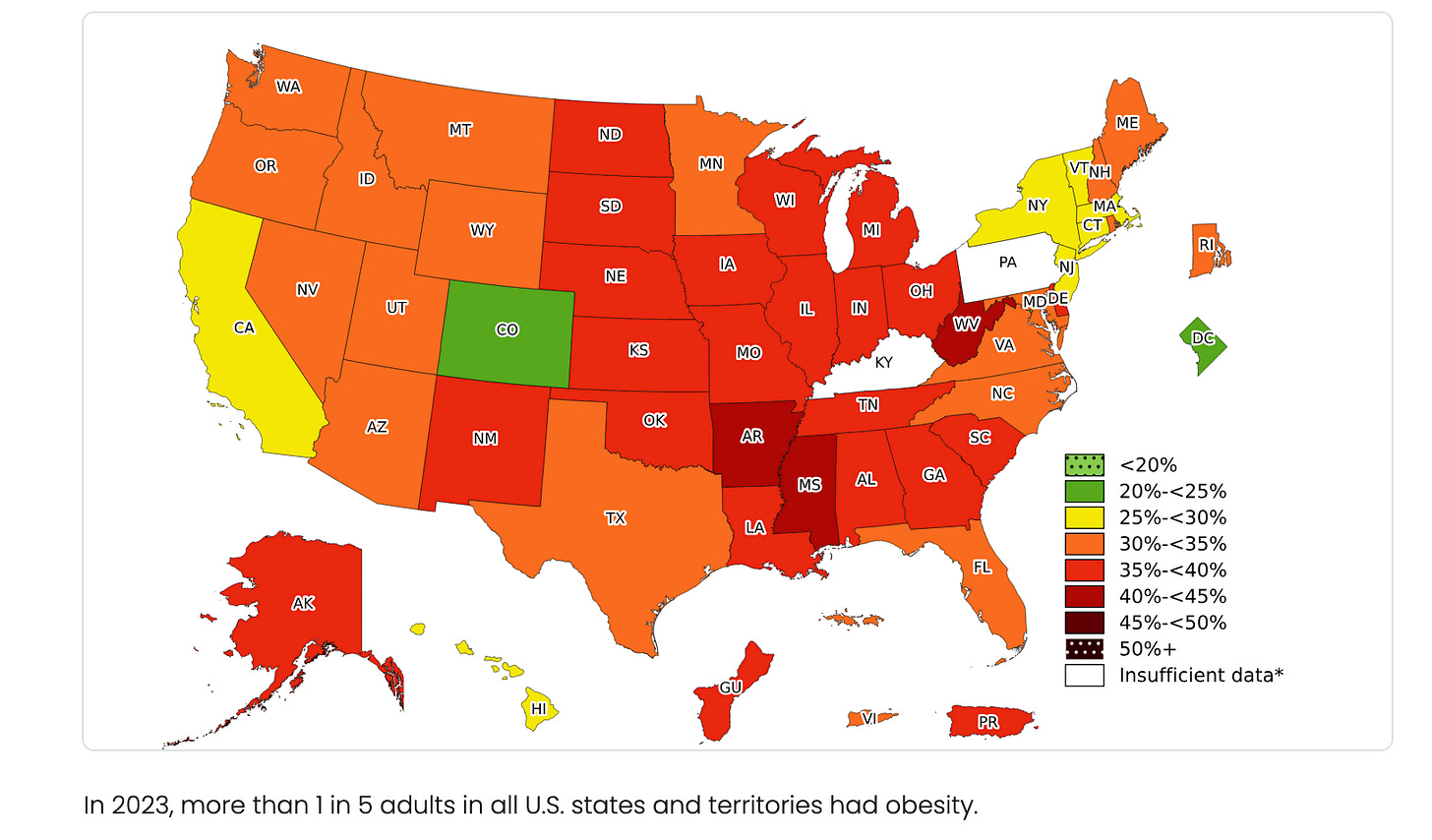

Food insecurity is followed by higher levels of obesity and diabetes everywhere, especially among North America's free trade partners. I will focus on this relationship in my later columns. However, looking at the patterns of food insecurity and obesity rates among the US states could give you an idea about the similarities between the two.

Source: USDA

Source: CDC

During Trump's first term, NAFTA was “modernized” with more compromises from Canada and Mexico. Key changes included increased environmental and working regulations, incentives for automobile production in the US (with quotas for Canadian and Mexican automotive production), more access to Canada's dairy market, and an increased duty-free limit for Canadians who buy US goods online. The new treaty came into effect on July 1, 2020, and was named USMCA. Only five years after the new treaty took effect, President Trump’s first act when he came to power for a second term was threatening Canada and Mexico with a 25 percent tariff on imports by pointing out the trade deficit with the trading partners.

Losing its biggest trading partner is a significant threat to Canada. According to Statistics Canada, in 2024, the United States was the destination for 75.9 percent of Canada's total exports and the source of 62.2 percent of Canada's total imports. In the agri-food sector, a similar profile arises. According to the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), 2023 the U.S. was Canada's most prominent agricultural trading partner, buying 60.3 percent of Canadian exports and supplying 56.8 percent of Canadian imports.

Trump continues his rhetorical attacks on Canadian sovereignty by making Canada the 51st state. While one can dismiss these as the disjointed twaddle of a populist leader, we cannot imagine how they will shape the politics of the street in all three countries. I wonder what would happen if the victims of corporate and state restructuring and free trade globalism could see how similar the patterns have victimized them all.